Kathy Moore is not your typical seagoing cowboy, and not just for the obvious reason that she’s not a boy at all.

Kathy earned her spot on Heifer International’s roster of floating cattle wranglers at age 16, when she spent her summer vacation plus some helping her father deliver 19 Holsteins and a Guernsey to postwar Japan. Her Pacific odyssey included the requisite sightseeing and meetings with recipient farmer families. But her visit was unusual in that it was a father-daughter team effort, and also that Kathy stayed in Japan for more than two months. Her epic summer vacation gave her enough time to explore, make friends and nurture what would become a lifelong dedication to the Far East and its people.

Preparations for the trip started well before their July departure date. Kathy remembers her father, Donald Baldwin, sending off reams of letters to fellow Heifer supporters at farms and churches throughout the Pacific Northwest in hopes of securing funding and donations. Service and giving were always a priority for Baldwin, a Methodist minister in Tacoma, Wash., who supported the Heifer cause from its earliest years. All four of his children were supporters, too.

“When you grow up a minister’s child, you’re always thinking about service, about what else you can do,” Kathy said.

Of the four Baldwin children, Kathy was the clear choice to be her dad’s right-hand man for this project. Her brothers were too young, and her older sister was married and had a new baby. Kathy was a member of her 4-H Club livestock judging team and often visited her uncle’s dairy farm, so her dad enlisted her that winter and spring for weekend visits with farmers across the Pacific Northwest who might donate a cow or give a discount. And then in July, with 20 cattle collected and passage aboard the Hoosier Mariner booked, Kathy set off from San Francisco with her father on her first overseas trip. Her eyes still widen when she talks about that summer.

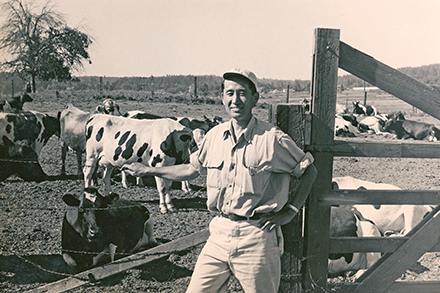

“It was the chance of a lifetime,” she said. Photos show young Kathy on the docks in snappy heels and a suit, perhaps not the best wardrobe choice for what would turn out to be an athletically demanding day. The longshoremen and deck hands, inexperienced with livestock, were spooked by the cattle and refused to load them. And Kathy’s father was busy with the dicey task of loading the cows onto a flying stall that was then lifted by crane. Although the men bristled at having a female on the deck, they ultimately stood aside as Kathy calmly led the imposing animals from the flying stall to their sheds on board.

She remembers that the 10-day trip was largely uneventful. A small library on board helped her pass the time, and her father held some small chapel services for passengers and the captain. Reporters were at the docks waiting to interview and photograph them when they landed at Yokohama Harbor.

With the animals sent off for a two-week quarantine, Kathy and her father set off to Tokyo for the World Christian Education Convention, where Kathy babysat some of the participants’ children between stints of sightseeing. After the conference, father and daughter headed north to meet Phil West, the son of Heifer founder Dan West.

Phil West had arrived with his own shipment of donated animals two weeks earlier. Although the animals she’d traveled with were still in quarantine, Kathy and her father would see Phil West deliver his shipment.

All of the Heifer animals were bound for Hokkaido, Japan’s second largest island. Located on the northern end of the country, Hokkaido has a short growing season and long, icy winters. In the postwar years, with Japan’s economy in tatters and few paying jobs to be had, the government relocated many people to this sparsely populated island and gave them acreage to farm.

“These people came from the central and southern parts of Japan where they could grow warm-weather crops,” Kathy said. “They had to learn to farm in a cold climate.”

Farmers had to be resourceful in such unfamiliar conditions, and there was lots of trial and error. Kathy remembers seeing sweet potato vines growing atop thatched roofs. Initial attempts at growing corn failed, but the farmers learned to use the stalks for silage. The chilly climate they suddenly found themselves in was suitable for dairy cattle and timber production, if little else. So the farmers marketed their dairy products, which were novel in Japan at the time. Ice cream proved an easy sell, and Kathy remembers feeling optimistic that Heifer’s dairy cattle would be lucrative resources.

“We wanted to help bring back the health of these people and their communities,” she said. “It makes the soul feel good, you know.”

The itinerary was a full one, sending the father-daughter team not only to the farms of Heifer project participants, but also to visit with a number of Christian church congregations, local dignitaries and students. The piece of the trip Kathy remembers as both the best and worst was the visit to Hiroshima, where she saw reminders of the 1945 atomic bomb attack everywhere. During communion at a church service, for example, she looked to the left and right and noticed that almost all of the adults around her were crossed and blotted with scars left from the burns they suffered.

That day she and her father visited the museum, where they saw sheets of human skin so badly burned that it had peeled off. It was summertime when Allies dropped the bomb, and most people were wearing yukatas, traditional cotton kimonos marked with large flower prints. The patterns from the kimonos were still visible on the burned skin, Kathy said. “The blast was so bright it imprinted images onto their skin like it had been tattooed.”

She also remembers walking across a concrete bridge that was among the few structures left standing after the blast. Shadow imprints of people who had been on the bridge when the bomb fell were still visible, like a photo negative.

Kathy returned to the United States one month late for her junior year of high school, but it’s clear that the trip taught her more and made a bigger impact than anything she might have missed in class. She still keeps copies of all the correspondence her dad sent off before the trip, along with itineraries, maps, slides, trip reports and photographs. “When you’re young, it makes a huge impact to see real need. American children don’t often see that,” she said.

Before going to Japan, Kathy planned to focus on studying animal science in college, but she decided to major in anthropology and Far Eastern studies instead. “Because of my trip, I decided to focus more on the people.”

And when she married an Arkansan and moved from Seattle to Little Rock, she found another place to put her experience and expertise to use. The late 1970s saw an influx of Laotian refugees to Arkansas. These families needed help learning a new language and figuring out their place in a landscape entirely new to them. Kathy volunteered, eventually helping 20 families enroll their children in school, get driver’s licenses and find jobs. Kathy and her husband took one family into their own home. The daughters, one three and the other just four months old when they moved in, are now adults and remain close to Kathy today. Busy with her work with Lao families, Kathy didn’t even realize the same Heifer Project for which she volunteered in her youth was now headquartered in her new hometown. She made the connection during an international-themed street fair where she spotted a Heifer booth and stopped by to share her story about her trip to Japan.

“Oh, that blew them out,” Moore remembers. Kathy stepped up for Heifer once again, volunteering full time for four years before officially joining the staff. One of her first responsibilities at Heifer was to help sort out, archive and preserve the boxes of shipping records, photographs, letters and other memorabilia from Heifer’s earliest days. It’s a job for which she was uniquely qualified.

Though now retired, during her time at Heifer International she also helped process donations so the organization could continue its mission. Mustering enthusiasm for the work was never very hard for Kathy because she knew it was truly helpful to people in need. In the summer of 1958, Kathy said, “my mindset was that I wanted to help people get out of those desperate situations. I’m still going through it. The same thing that helped then, helps now: farming, a sustainable life."